EduFocus #15: Raising the Standard: School Improvement Lessons From Three Projects in Jamaica

Over the years, many schools have been involved in improvement projects that sought to enhance the quality of the teaching and learning environment to ultimately realize the motto, ‘every child can learn, every child must.’ Among these projects were the Jamaica All Age School Project (2000 - 2003), the New Horizon Project (1999 - 2004) and the Expanding Educational Horizon Project (2005 - 2009). While the Jamaica All Age School Project (JAASP) focused on providing better education in 48 schools located in disadvantaged, remote, rural communities, the New Horizon Project (NHP) and Expanding Educational Horizon (EEH) focused on approximately 72 poor performing schools across Jamaica. All project schools were characterized by a high number of students considered to be at-risk, due to high rates of absenteeism, low rates of achievement, insufficient resources for learning, a lack of student-centered instruction, and low parental involvement.

GAINS

These project schools made gains in the school improvement process by fostering a collaborative approach to problem solving and monitoring outcomes of strategies employed . Some areas of improvement included teaching methodology, students’ literacy and numeracy competency, school improvement planning, and management.

JAMAICA ALL AGE SCHOOL PROJECT

JAASP used “inter-active, learner-centred methods in all classes” with an emphasis on the needs of students with exceptionalities and the development of literacy and numeracy (Daniel, 2003). Interventions include, but are not limited to, the introduction of the Literacy Window, special needs screening, training to develop skills in relation to school improvement planning, curricula, literacy, numeracy, special needs, and learning support. By the end of the project, 11 out of 12 schools surveyed decreased the number of at-risk students by more than 10%. In 2000, only eight out of 48 schools achieved the national average in all five subjects of the Grade Six Achievement Test (GSAT). In contrast, of the 24 schools surveyed in 2003, six achieved scores above or around national and regional averages, and 14 schools increased the average score in four of five subjects.

students with exceptionalities and the development of literacy and numeracy (Daniel, 2003). Interventions include, but are not limited to, the introduction of the Literacy Window, special needs screening, training to develop skills in relation to school improvement planning, curricula, literacy, numeracy, special needs, and learning support. By the end of the project, 11 out of 12 schools surveyed decreased the number of at-risk students by more than 10%. In 2000, only eight out of 48 schools achieved the national average in all five subjects of the Grade Six Achievement Test (GSAT). In contrast, of the 24 schools surveyed in 2003, six achieved scores above or around national and regional averages, and 14 schools increased the average score in four of five subjects.

School attendance

In 2000, the average school attendance was 61 percent – higher among girls, and in some instances, the gender gap in attendance was 15%. In one school, where average attendance was 67 percent, parents explained students’ absenteeism was due to lack of money and lunch, rainfall, and children’s responsibility to help in the home or field. In response, Fruitful Vale All Age provided lunch to 74 of these students on a daily basis and communicated with their parents. After one term, the attendance of the target group increased by 32 percent.

NEW HORIZON PROJECT

Through NHP, a menu of 10 project interventions were selected depending on the school’s need. In 1999, Juarez and Associates noted that “very few schools appear to be in stated position of readiness to deal with literacy and numeracy in their schools.”( Lockhead, Harris, Gammil & Barrow, 2006). When NHP schools were compared to equivalent non-NHP schools, the former scored higher on writing (GSAT’s communication task 1) and mathematics. According to Lockwood et al (2006),“the share of NHP with mean scores greater than 3 points (on a 6-point scale) increased from 4 percent in 1999 to 53 percent in 2004 while their non-NHP counterparts increased from 7 percent to 39 percent.” Likewise, NHP schools experienced an increase from 26 percent of schools having a mean score of 30 points or more in 1999 to 41 percent in 2004. However, their non-NHP school counterpart, only experienced a 1 percent increase over the same period.

EXPANDING EDUCATIONAL HORIZON PROJECT

EEH built on the lessons learned during NHP. By December 2008, 62 schools successfully graduated from the programme having met stipulated criteria, which included:

• acceptable performance in literacy at the grade-four level, maintained over two years with 65 percent of students at mastery level;

• acceptable performance in mathe-matics at the grade-three level, maintained over two years with 65 percent at the mastery level.

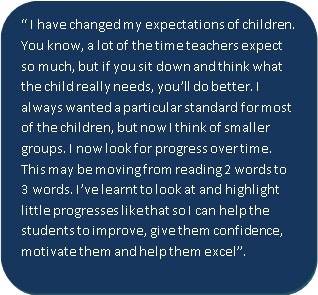

The gains made by these schools resulted from school leaders and the teaching staff’s commitment to making adjustments in teaching practice, school management, and school community relations. Lessons from the NHP experience include the recognition that school improvement necessitates a change in deep-rooted culture. The continuum of change occured in three stages as teachers transitioned from traditional systems based on memorization to more active, participatory learning.

Stage 1: teachers experience fear and resentment, combined with the fact that the new methods are sophisticated and time-consuming

Stage 2: Teachers becoming conversant with the new jargon and may begin to try some new ideas. However, without ample support in the classroom, many find new methods difficult and may abandon them.

Stage 3: Many teachers still have not mastered the new strategies, but they are on their way. With adequate training and support, teachers come to see the advantages of the new methods, find that they enjoy them and that their students are more enthusiastic.

Establishing these changes required the implementation of responsive school improvement plans (SIP).

SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT PLANS

The SIP process adopted by JAASP was “designed to foster a close relationship between the school and community through the participation of all stakeholders” (Flett, 2004) As a result, learning goals that focus on students’ achievement and personal development, as well as associated action strategies, were jointly decided by schools and their stakeholders. To achieve this, schools invited a wide range of stakeholders to participate in developing a shared vision and established a School Improvement Action Group (SIAG) to support the planning process.

The role of the SIAG

This group was carefully recruited by stakeholders and included a representative from each stakeholder: principal, teacher, student, community member, parent, and school board member. Once data had been analyzed to determine strengths and weaknesses, learning goals were prioritised, and efficient action strategies were identified to ensure success. Each action strategy had a strategy manager who monitored the group’s timeline and gave regular reports to the SIAG. The SIAG collated all progress reports and made them available to all stakeholders.

NHP schools employed a similar participatory process. Though many parents and teachers did not understand the importance of the process and found it difficult and time-consuming initially, they came to appreciate it. It “provided them with a focus for their efforts and a way to know when they have achieved their goals.”

EEH defined partnership as “an alliance between two or more parties to jointly define a developmental problem and contribute to its solution, whereby partners share resources, risks and rewards.” Participatory SIP is a powerful antedote for poor performing schools as it fosters school community partnerships that support learning goals and students’ academic and social development.

Visit our Help Center to find answers to frequently asked questions.

Visit our Help Center to find answers to frequently asked questions.