The Roots of Crime in Jamaica - the

Crisis in the Rural Economy

From the Homecoming Lecture delivered by Professor

Don Robotham, CUNY Graduate Centre Homecoming Honouree

|

I want to use this occasion to discuss

an issue which continues to afflict our society, which is

the issue of crime. In doing so, it is not my intention to

enter into the current heated debates about the measures

to be adopted to address this huge problem in the short

term. I would only urge great caution in how we proceed:

we must not lose sight of the fact that short-term

measures have very real medium- and long-term

consequences. The broad social and political consequences

of draconian measures taken in desperation today are

surely not going to disappear tomorrow or the many days,

months, and, indeed,years after tomorrow.

I also wish to highlight the very important research which

scholars at The University of the West Indies continue to

conduct on the crime issue. There is the foundational work

of Professor Tony Harriott, especially his recent work

stressing the importance of effective investigation of

crimes. There is also the work which Horace Levy, Dr.

Elizabeth Ward and Deanna Ashley have done on Peace

Management and Violence Prevention. This work clearly sets

out in some detail methods which can be used to intervene

at crucial points in the lives of young people to reduce

the likelihood of their turn to crime.

I also want to mention the recent work of Professor Wayne

McLaughlin to set up a forensic science program. This is a

highly important initiative which will make a very

practical contribution to addressing the crime issue.

Finally, I wish to point outthe significance of the

brilliant work by Dr. Herbert Gayle. Unlike the work

byothers, this is principally qualitative work using

anthropological methods.

To me, one of the great values of this work is that it

offers us profound insights into the process by which a

young person sets out on the road to crime. When read

together with the autobiographies of offenders (which

exist) we can see in some detail and at a very personal

level, how an otherwise very normal young man at a certain

point and under specific sets of social circumstances,

takes a turn to crime which others around him might or

might not.

This detailed work offers us deep insights as to how the

process works and provides us with important and

invaluable clues as to how to intervene to reduce the

likelihood of this wrong turn.

There are many other scholars at The UWI who have been

labouring in this vineyard for years – Professor

Denise Eldemire-Shearer, for example. I hope they will

forgive me if I don’t mention them all. I only choose

those above as the work with which I am most familiar and

whose findings seem to me to be immediately useful.

This many-sided and high quality research is not

recognized enough by the wider society – the canard that

UWI is not contributing to Jamaican and Caribbean society

continues to hold sway in some surprising quarters. It is

manifestly false and we have to redouble our efforts to

ensure that the society becomes more aware of this work.

What is true, however, is that work rarely finds its way

into public policy. Something is profoundly wrong when

this highly relevant body of research and public policy

simply exists side-by-side without the first having much

impact on the second. Indeed, it is worth researching the

policymaking process in Jamaica as an issue in itself – we

need to understand what the bottlenecks are and how to

remove them.

Instead of speaking to the immediate issues, I want to

look at what I suggest to be one the underlying causes of

our crime problem: the crisis in the rural economy.

I want to begin by reviewing the data on the crime prone

group in our society. This is the population in the

15-29 age group—particularly men, who are responsible for

at least 80% of all the crimes committed, homicides in

particular. As we know, but is persistently

forgotten, Jamaica has had a low birth rate for some time

now. The vision that many perversely cling to, of a

society in which children are being produced and strewn

about at an alarmingly high rate, has not

corresponded to reality for at least 10 years.

This low birth rate is the reason why the Jamaica

population has not budged much—remaining at roughly 2.7

million persons over the decade. Indeed, one consequence

of this declining birth rate is that increasingly we are

facing all the problems of aging societies—pressures for

greater health care expenditures on the elderly, a greater

incidence of chronic diseases, labour force problems,

different patterns of dependency and so forth.

|

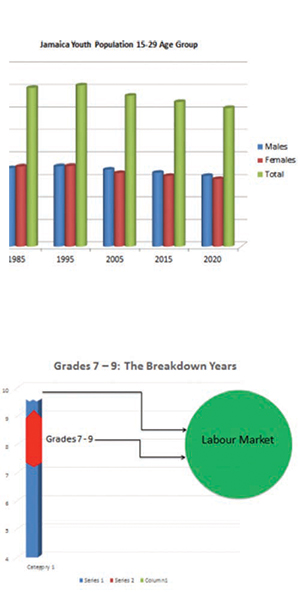

The result of this falling birth rate is apparent in the

following table: The 15-29 age group rose to a peak in

1995 but has steadily declined thereafter. By 2020,

according to my projections there should be about 100,000

fewer persons in that age group than existed in the peak

year more than 20 years ago. Both males and females

declined, with the decline in females slightly higher than

that of males. Based on these data, it would have been

logical to project that our crime rate, including our

homicide rate, would have gone down. But instead the rates

have shot up. What this tells us is that there is no

relief to be sought in these purely demographic type

shifts. Deeper forces are at work in, in effect, to

intensify the pressures on young people to commit more

crimes. What would some of these pressures be?

Firstly, this has to do with problems in our education

system and in our labour market. As far as our education

system is concerned, both our GSAT and CXC results as well

as the work of Herbert Gayle and Elizabeth Ward suggest

that there aregrave problems at the 7-9 grade levels. I

call these the breakdown years: If we carefully analyze

the performance of our children in the annual GSAT exams

and compare the performance at CXC levels we will see that

there is a clear relapse in the education system between

the two levels. The data that we have suggests that, if we

could sustain the levels of performance achieved in

English and Mathematics at the GSAT level, we could

achieve about a 15-20% improvement in our educational

quality at the point of graduation. Studies of individual

schools confirm this conclusion. It is clear that

there is a relapse in educational performance right after

the GSAT. It is as if the parents and the children having

made the supreme effort at GSAT (huge expenditures on

private lessons, other intense training, acute family

pressures) heave a sigh of relief feeling that their job

has been done and it is now up to the child and the high

school teacher to deliver the goods.

Rural schools have a particular problem in this regard. In

one case with which I am familiar, after GSAT, the

children go on from the primary school in the same

township to the local high school. Their performance in

the GSAT is weak but their performance at the CXC is truly

dismal. What is behind this? Here we come up on old

patterns of rural family socialization and political

economy. It is well-known that at around the age of 11/12

(and sometimes earlier) the child will often be given some

chickens or a goat of their own to look after. Boys may be

given some banks of yam to cultivate and to keep the

income as their own. They begin helping family members who

go to market or with other economic activities (‘ductor’

on a bus or sideman on a truck). In other words, the

children begin to enter the labour market during this

period in a haphazard fashion. Absenteeism grows, in

addition to all the problems of adolescence, affecting

boys in particular. We see it in the lamentations around

the behavioral problems of our children in this age group

on public transportation. The children leave school early

with limited literacy and numeracy and are unfit for

anything but unskilled general labour. This is a huge

problem, and as the work of Herbert Gayle and Elizabeth

Ward, Deanna Ashley and others shows, these are crucial

years in the turn to crime. Yet, again, we know from the

work of the Violence Prevention Alliance, it is perfectly

possible to develop effective programs to counter this

breakdown. Their “10-Point Plan for Violence Prevention”

is based on careful research and practical experience and

offers us simple but effective solutions to reduce the

problems in these breakdown years.

Here it is necessary to make a side commentary on early

childhood education. Sometimes it seems that this is

presented as a panacea for all the problems of our

education system. The thought seems to be that if one

could only fix the system at the point of entry then the

benefits would flow smoothly through to the rest of the

education system, up to the CXC level. This is an

illusion. Every level in the education system counts. For

many reasons, we cannot rely on the very important

improvements in early childhood to carry the burden of the

weakness of the system in the immediate post-GSAT years.

Those years are a problem in their own right and require

their own distinctive solutions. In fact, if I were to

single out a particular segment of the education system

for priority attention there is no doubt in my mind that

these breakdown years of grades 7-9 would be the prime

area of focus. If we focus more on these years and address

the difficulties that arise there it won’t solve

everything but will certainly take us to a place better

than where we are today. Again, one must ask the

question—why isn’t this work more applied by our

policymakers? What are the forces which are obstructing

their use?

As pointed out above, our children begin to enter the

labour market in significant numbers in these breakdown

years. An immediate consequence of this is the

relatively high youth unemployment rate which is in the

region of about 20%. But more important than the gross

unemployment rate is some characteristics of the

youth unemployed: about 45% of all youth unemployed are

long-term unemployed. Most striking of all, about 63% of

the long-term youth unemployed have never worked. However,

and this is most important, about 27% of them have 4 years

or more of high school education but no certification.

NO WORK EXPERIENCE

We should reflect on those data for a moment. What they

are saying is that, in the approximately 650,000 young

people in the 15-29 age groups, we have a large pool of

young people who have no experience of work whatsoever.

Large numbers of them have stopped looking for work

completely and have left the labour market altogether. It

is striking that STATIN labour market survey data for 2014

indicate that about 53% of those who are able to work but

not seeking, give as their reason thatthey “don’t want

work.” It is important to be cautious here and to

emphasize that they are NOT saying they “don’t want to

work.” This is not a statement about the general value

that they attach to work. It is a situational statement

which is highly contextual: I interpret it to mean that,

given existing low wage levels, especially for labour

market entry-level jobs (for example in the tourist

sector), remittances and other forms of family support,

the options of hustling legally and illegally, all things

considered, in the concrete circumstances of their life in

Jamaica, not working is the better option. Take some of

these same people out of this context— for example, by

migration—and their hitherto dormant work ethic somehow

blossoms!

However one interprets this, the more important point is

that thousands of our long-term unemployed youth who have

dropped out of the labour force have been in high school

for some years and do have some education but no

certification.

In other words, the situation is that a very large number

of our youth do not earn a regular income in the labour

market yet have had their aspirations raised by being

exposed to more education, however limited. This exposure

is of course greatlyincreased by social media and the

whole cell phone culture producing a combustible mixture

with which we are confronted every day. It is well known,

from the experience of Nigeria, for example, where high

levels of graduate unemployment have produced a

proliferation of cyber crimes which have severely harmed

that country’s international reputation, that this

combination of chronic youth unemployment and some

education is a formula for social disaster. Sadly, Jamaica

too has embarked on a comparable road. There is no doubt

that our case has important similarities to the Nigerian

one and that, apart from the lotto scamming which is the

obvious example, we are already facing an increase in

crimes— for example ATM password theft—which reflect a

higher level of education. Below is an excerpt from the

threatening letter written by extortionists in Manchester

and Clarendon and published in The Gleaner:

“If you feel the need to get the police involved or

private security to protect your business or fight this

proposal, feel free to do so, because if they apprehend

the subject that is sent to you, you (the owner, manager,

employee) will be killed and your family will be at high

risk of being murdered in the most gruesome way."

This is written in sophisticated (if somewhat wordy)

English using a complex sentence structure and pompous

vocabulary (“apprehend”) with all the punctuation properly

and carefully in place, almost as if it went through a

process of drafting, copy editing and redrafting. There is

even a slight touch of sardonic humor and irony—“feel free

to do so”—this is no hastily scribbled note from an

illiterate criminal. We are face-to-face with a writer who

understands how to deploy nuances of the English language

to evoke a particular emotional response from the reader

and who even takes a certain pride in showing off these

skills. The long and grammatically perfect threatening

sentence is clearly written by someone with at least a

tertiary education—my guess would be a graduate in the

Humanities since Social and Natural Science graduates are

not renowned for their prosewriting skills!

|

THE RURAL ECONOMY

But these general problems of our youth population are

acutely intensified for the rural youth since we know from

many Surveys of Living Conditions that poverty is most

prevalent and deepest in the countryside, principally in

the hills in the interior of parishes such as St. Ann,

Hanover, Westmoreland, and St. James. This takes me to the

specifics of the situation in the rural economy. Here I

begin with some data setting out the decline in the

production of sugar and banana, the two crops which have

sustained the population for centuries. From a high of

over 400,000 tonnes in the 1960s, sugar production has

drastically declined to about 130,000 tonnes in 2014-2015.

It should be pointed out that, as others have done, that

from the 1960s this sugar problem was apparent, especially

to the principal investors Tate & Lyle. This is why they

took steps to sell out to the Shearer government before

1972. It was apparent then that the 400,000 tonnes crop

was won by bringing entirely unsuited lands into

cane production and that the high figure obscured the low

sugar cane yields which obtained.

It should also be noted that this collapse of sugar is not

peculiar to Jamaica: Puerto Rico, Cuba and the Dominican

Republic have also faced this problem which has wreaked

havoc with rural life throughout the entire region. Since

2002, Cuba has closed 71 of their 156 sugar mills and

taken 62% of the land hitherto devoted to sugar

cultivation (about 4 million acres), out of production.

The result is that employment in the sugar industry in

Cuba is reported to have declined substantially leaving

about 200,000 persons employed from approximately 500,000.

A similar problem applies to banana production in the

region. In Jamaica, this also fell dramatically up to

2006-2007. Since then there has been some limited recovery

but not enough to improve the lives of the people in the

parishes which traditionally depended on these crops for

their livelihoods. Again, it should be noted that the

decline of bananas is not peculiar to the

Caribbean—Honduras has also suffered from changes in this

sector: between 2003 and 2013, banana production declined

by 40% and there was a similar collapse in coffee

production. The crisis in the Honduran and Central

American countryside has been an important driver of the

extremely high homicide rates (67 per 100,000) in those

countries and the high rate of external migration to the

United States.

It should be recalled that Arthur Lewis, in his famous

article on ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies

of Labour’ published as long ago as 1954, anticipated this

problem of the crisis of the rural economy and its chronic

‘surplus labour’ problem. In other words, Lewis saw

clearly that the postwar Caribbean rural economy was not

viable and that political independence would be

meaningless without a transformation in this situation.

Looking back, it seems to me that the depth of this

problem was insufficiently grasped then by our

politicians, policy makers and the general public.

Lewis’ answer to the crisis was a program of tax holidays

to attract foreign investment into manufacturing which

would then produce for the export market. This, in his

view, would siphon off the excess labour from the

countryside and also keep urban wage levels fairly low,

providing even more of an incentive for inward

manufacturing investment. Parts of this Lewis policy were

followed in both Jamaica and Puerto Rico but without the

export-led development thrust. It was left to the newly

industrializing countries of Southeast and East Asia to

pursue the Lewis model in its fullness and to its

ultimately successful conclusion.

But, and this is the point, the Lewis model didn’t really

speak to the issue of revitalizing the rural economy so

much as it did tothe creation of a new urban economy based

on manufacturing. In his model, the rural economy remained

very much a residual and it is not at all clear how it

would have been modernized, if at all, or whether it would

simply linger on as a diminished labour reserve appendage

for urban manufacturing where the real economic action

would be. It’s worth noting that in South Korea, often

cited as the model Lewis development experience, the

problem of rural poverty and stagnation and a large food

import bill continued to plague the country even into the

1980s when urban industrialization had already become

considerably advanced. What this suggests is that the

problem of revitalizing the economy in the countryside is

a very difficult one to resolve, even under the most

advantageous circumstances of rapid industrialization.

The impact of the decline of the old export crops is

clear. What of domestic agriculture? A look at Jamaican

domestic crop production (yam, vegetables, condiments)

shows that this has either maintained the same level of

output or declined somewhat since a high in 1996. There

are a couple of points worth noting here: First, in

general, there has been no expansion of domestic

production to take up the slack following the decline of

the traditional export crops. Further, it is striking that

domestic agricultural production is concentrated in three

parishes: St. Elizabeth, Manchester and Trelawny.

Parishes such as Hanover, St. James and Westmoreland (3%,

4%, 7%) produce relatively small amounts. Very clearly,

domestic crop production is still principally oriented to

the-old internal marketing system going back to the 18th

century and is in almost complete disconnect, for example,

from the tourist sector. In a more balanced process

of economic transformation, the development of a new

sector such as tourism would be integrated with others and

indeed, provide a new expanding market for the commodities

being produced in the countryside. But such has not been

the case.

On the contrary, if one looks at the expansion of tourism,

the disconnect between tourism and the food producing

sector becomes even more apparent. From a low of 35% of

export earnings, tourism is now at about 50% (the sharp

dip reflects the 2008 Great Recession). Despite that

15% points growth in tourism food production has basically

remained flat or trended down somewhat. All indications

are that tourism revenues will continue to grow in the

future as our visitor arrivals increase steadily.

However, tourism is on the coast where the glittering new

hotels are being built. There is no glitter in the hills

where poverty and severe economic hardship reign. A

profound, and one could even say, brutal spatial

re-orientation of our centuries old rural economy, is

complete. The notorious ‘plantation economy’ of the

Caribbean, is no more. A largely coastal economy almost

completely dependent on tourism and services has replaced

it.

From the West End and Seven Mile Beach in Negril on the

left, to Hopewell on the right, the coast is alight with

one hotel after another. When one looks at the old sugar

plains of Westmoreland and St. James and the banana lands

of Hanover, the picture is one of darkness and

abandonment.

One has to be careful not to draw too straight a line from

the economy to crime—it doesn’t of course work quite like

that. Nonetheless it is striking that, outside of the

urban centers, it is precisely in the abandoned

parishes of Hanover, Westmoreland, St James and Clarendon,

that we find the rural murder rate shooting up. So far for

2017, the murder rate in the above three parishes has

increased from what it was in 2016: from 1 to 12 in

Hanover; from 6 to 11 in Westmoreland; and from 5 to 12 in

St James. My expectation is that this will continue to be

the case until we can find a way to restore economic

viability to the hills of rural Jamaica.

|

SOME SOLUTIONS

The revitalization and transformation of our collapsing

rural economy is precisely the challenge facing us. In

that regard, let us take a brief look at some initiatives

which have been taking place recently in rural economic

transformation. These are examples of small scale tourism

development in the countryside, far away from the luxury

villas and mass tourism allinclusives of sun, sea and

sand.

My approach is to look at examples ofwhat is actually

taking place and to see what can be learned from this

rather than to prescribe abstractly and from the top down.

Although there are a wide range of new economic activities

occurring in the hills, I identify two models: the first

is the single entrepreneur model heavily dependent on

Airbnb. The second is a community tourism model which

works closely with a group of US colleges.

The first case is Jay’s Guest House located at Hagley Gap

on the St. Andrew/St. Thomas border.

Jay’s is a family business run by Aden Jackson a young 25

year old graduate of Mico who teaches at the local school

and who was born and raised in the area. He has a staff

who are largely members of his immediate family.

The business has been in operation for one year and gets

visitors from Germany, Brazil, Canada, Spain, Malta,

Bulgaria and the United States. Aden markets Jay’s through

Airbnb which, according to the Minister of Tourism

has over 1,000 Jamaicanproperties on site bringing in

about 32,000 tourists, many of whom stay in urban inner

city neighborhoods such as Trench Town, drawn by the long

history of musical culture.

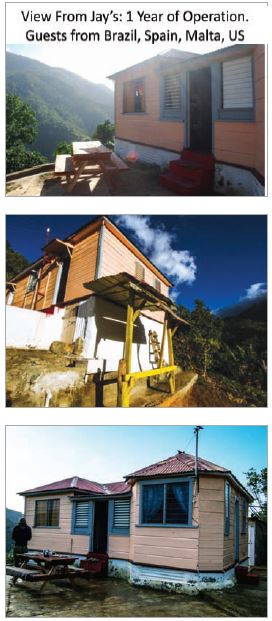

This takes us to the second model: the Community Tourism

Model operated by the Association of Clubs in Petersfield,

Westmoreland. One of the most remarkable things about this

model is that it is located in an area formally designated

a high crime hotspot by the police. Yet, they have been

operating since 2001 without a single incident or crime

against any visitor.

This model does not market through Airbnb but instead

works with AmizadeGlobal Service-Learning, an American

operation which organizes study abroad programs with major

US universities. This year, the Association of Clubs of

Petersfield will have visits from 15 universities,

including the University of Pittsburgh, Cornell and Rice,

with between 10-15 students coming in each group, many

being repeats.

Unlike the case of Jay’s Guest House, these students are

required to live in the homes of members of the local

community and to make tangible contributions to

Petersfield community life. They have helped to construct

rooms at the local school, build a local bus stop shed,

improve the local school library and generallyhelped to

improve the conditions of life of local citizens. All of

this ensures that the benefits of the visits are shared

widely in the community and local people have a vested

interest in ensuring that the visitors are protected and

will want to return.

The organizer of this venture, Mathias Brown CD, is a

highly experienced Frome sugar worker cooperative leader

with verydeep roots in the Georges Plain area and widely

known throughout much of Westmoreland. For Mathias, apart

again from wifi and proper plumbing, the most important

factor in the Petersfield success is security. He stresses

that this is the principal concern of the College

representatives and this is the most crucial area in which

constant vigilance is essential. It should be noted in

this regard, that the Association of Clubs are not naïve

about the presence of criminals in the community but

take appropriate steps to ensure that visitors remain safe

and secure. Without the broad distribution of benefits and

the deep knowledge of the community, they would not have

been able to have the success which they have achieved.

This model of community tourism which taps into the US

college market is not unique—Dr. Erna Brodber has operated

a facility with some similarities to this one but with a

stronger academic and cultural program stressing the

African-Jamaican heritage in particular. But, the

Association of Clubs are clear that theirs is principally

a business however and they therefore combine community

development work with standard tourism activities such as

organized trips to resort areas such as Negril in which

students partake of very traditional tourist type

activities.

CONCLUSIONS

What conclusions can we draw from all of this? Below is a

photo of Aden Jackson, the operator of Jay's. Compare him

to a young man from the hills around Lucea recently

charged with multiple murders.

Aden is 25 years old and the young man is 22. Both are

from the hills and both probably share many experiences in

common while growing up. At some point, the youth from

Hanover made a wrong turn. What caused it? How can we

avoid that going forward? Which one is to be the futureof

Jamaica going forward? Can we replicate the examples from

Petersfield and Hagley Gap in the Hanover hills?

There is certainly no shortage of a cultural heritage of

wider interest to all: this is the area of three important

slave revolts—at Argyle and Golden Grove in 1824 and Sam

Sharpe’s revolt in 1831-32. The area is alsoone of

settlement of post-emancipation Yoruba and Kongo people—a

result of the interdiction of the Slave Trade by the Royal

Navy. In terms of more recent history, Blenheim—the

birthplace of Alexander Bustamante is in the same general

region. There also were Portuguese settlers in the region

and not far away in Westmoreland is the old German

settlement at Seaford Town. There are therefore many

opportunities to develop a more culturally oriented

tourism.

To pursue such opportunities requires us to take a new

approach. First, it should be clear that we need a

transformation and revitalization of the rural economy. It

is not enough to study squatter settlements in tourist

areas which arise especially in the hotel construction

phase. More and better housing for hotel workers in

tourist towns is key but does not answer the questions

arising from the crisis of rural life.

Equally, while the macro approach to the economy has been

vital and we have made fundamental progress in that area,

now is the time to move beyond the purely macro GDP

approach. First of all the issue is not just GDP growth

but the quality of growth: who benefits, is it inclusive,

sustainable and responsible environmentally? The most

recent data on economic inequality in Jamaica done by the

IMF showed a Gini coefficient of .59. That is an

astonishingly high level of inequality which is socially

fatal, especially in a small society like ours. Further,

we need to take a more ‘meso’ approach to the economy and

look behind the gross metrics of national income accounts.

Careful studies of regional economies on the ground at the

parish level are urgently needed. It’s vital to remember

that there is no single solution to our rural crisis—

there are and will be many approaches and many models.

We have to give room for them all and not strive for an

artificial standardization of any single approach. Above

all, we need better and more detailed data, especially

with respect to our labour force and living conditions at

the local levels. The University of the West Indies and

our national and local political representatives are

well-placed to conduct this work. And we must ensure, as

we proceed with the research, that the lessons for policy

are incorporated into practical programs of reform for the

lasting benefit of the Jamaican people.

NOTES & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The data and charts in this paper were kindly made

available by a number of persons. I thank Elizabeth Ward

and the Violence Prevention Alliance, Horace Levy and the

Peace Management Initiative, STATIN and officers from the

Ministry of Agriculture, in particular, Sandor Pike,

Raymond Mattis and Sharlene N. Findley. I am particularly

grateful to Aden Jackson of Jay’s Guest House, Hagley Gap

and Mathias Brown from the Association of Clubs,

Petersfield for permission to use their photographs and

for their discussions of their pioneering work. I have

benefitted immensely from the wisdom of Professor

Mojubaolu Okome who introduced me to the relevant material

on crime and graduate unemployment in Nigeria. Arnold

Bertram and I have spent years discussing these ideas for

many of which he can rightly claim paternity.

|